Recently, there has been much discussion around the Black Lives Matter movement, systemic racism in the United States and around the world, and other issues related to race and representation. Just the other day, a scholarly communication blog I follow posted about researchers exploring issues around race. As a scholarly communication librarian, I have been reading not only on research around race, but about representation in research and publishing. Questions such as “who is doing the research?” and “who is being represented in publishing?” have come up. So far what I have discovered is that in scholarly communication, representation is disproportionately white.

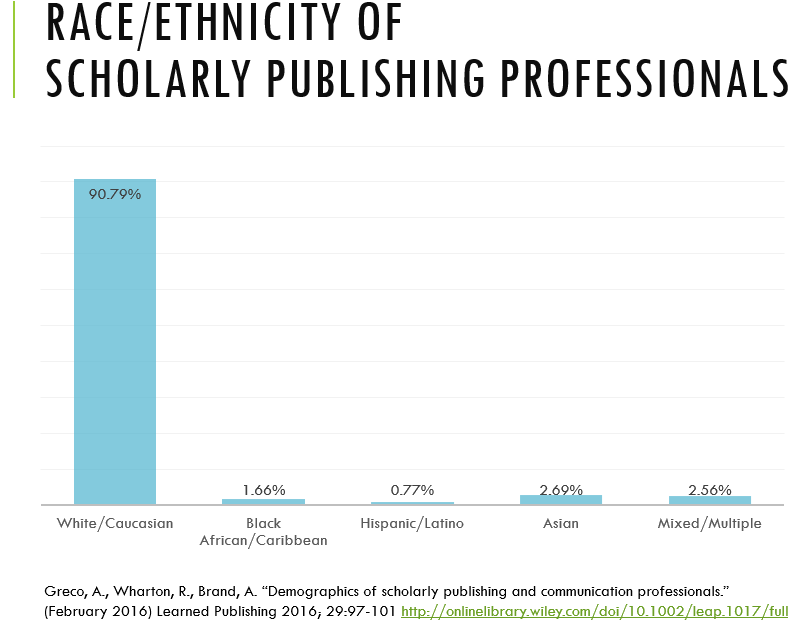

According to an article published in 2016, 90.79% of international scholarly publishing professionals are white, 1.66% are Black/African/Caribbean, 0.77% are Hispanic/Latino, 2.69% are Asian, and 2.56% are Mixed/Multiple (see graph 1 below). Now, you may think, “but 2016 was already four years ago, things have probably changed.” And I hope they are changing, but you may have realized in your academic career (whether you’re a student, staff, or faculty), that change takes a very long time.

So, why does it matter who is in scholarly publishing? Let us take a look at what happens when you are ready to publish your scholarly work as a book: You submit a proposal with a few chapters and the editor (or editorial board) decides it’s worth reviewing (see figure 1 at top of post). Your fellow academics review the work, if it’s accepted the book publisher puts together a package with marketing and sales projecting success, and it is approved with stakeholders at the book publisher. You and the book publisher sign a contract, the book gets published. Most likely, librarians will select and purchase the book to catalog it and circulate it and someday will decide if it should be removed from the collection or kept on the shelf. So, who has power in whether your work will get published? The publisher, your fellow academics, and whether your book is purchased by the library is decided by librarians.

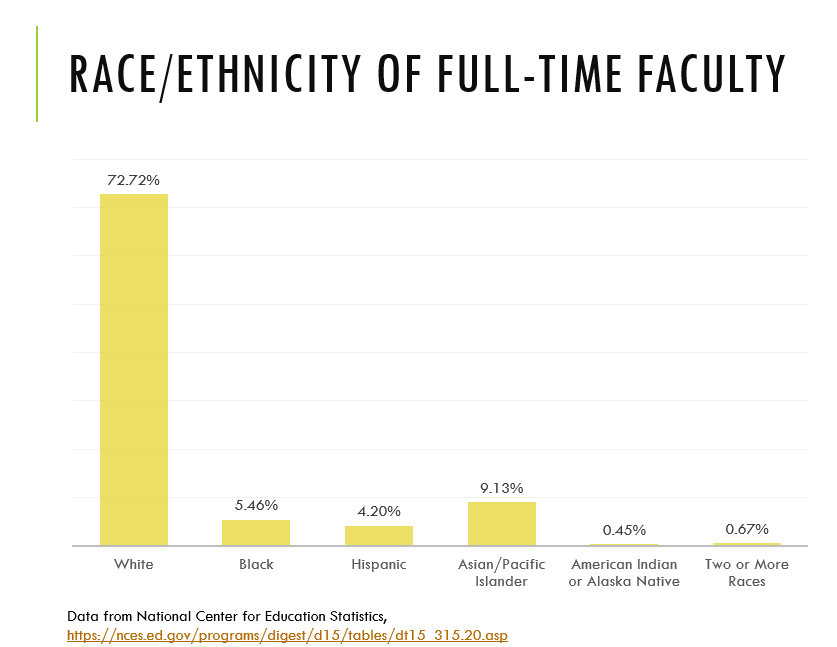

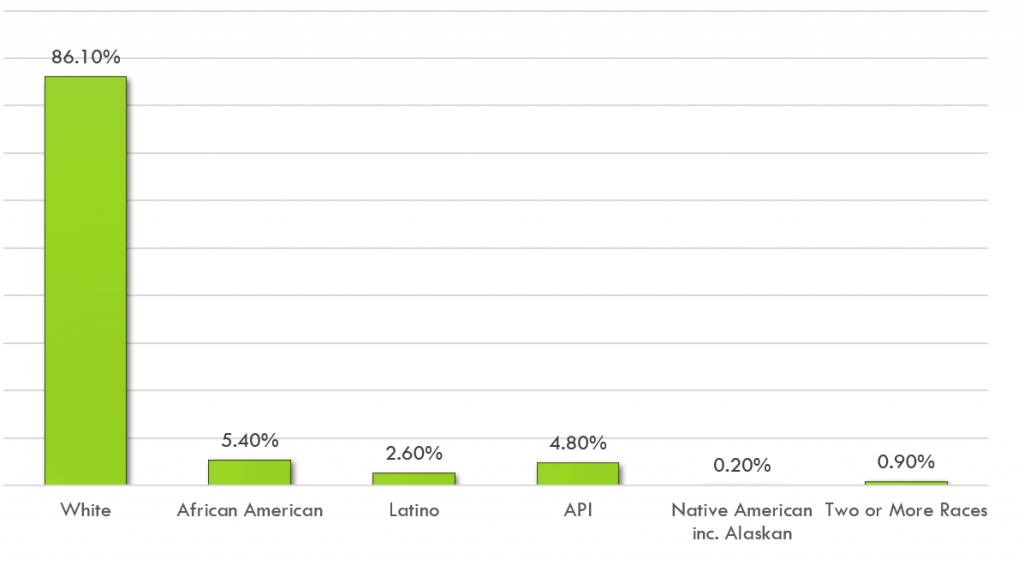

We have already looked at race/ethnicity in publishing, but what about academia and the libraries? According to federal statistics, full time faculty in the United States are 72.72% white, 5.4% Black, 4.20% Hispanic, 9.13% Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.45% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.67% Two or More Races (see graph 2). Similarly, statistics gathered by the American Library Association, demonstrate that higher education library professionals are 86.10% white, 5.40% African American, 2.60% Latino, 4.80% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.20% Native American including Alaskan, and 0.90% Two or More Races (see graph 3).

Here is my question: the United States is not made up of 70-90% white people, so why are faculty, librarians, and publishing professionals? This might be a fairly obvious question to ask, but I think it’s worth asking, and then, hopefully, I hope libraries, academia, and the publishing industry will make moves to be more inclusive. From my reading and conversations with fellow academics and librarians I’ve found a few hashtags to follow on twitter: Black graduate students and faculty are tweeting about their experience in academia with #BlackintheIvory and #BlackinIvory; publishing advances and contracts are being shared by authors via #PublishingPaidMe.While people of all races and ethnicities are able to publish, white folks are traditionally paid much more than authors of color. So, what can we do? Well, as a librarian and as a curious person, the first thing I like to do is read about a subject. And here’s the fun thing about reading, if you’re like me and reading nonfiction can get a bit boring (especially after reading for class or for another research project), nonfiction can be just as educational in terms of depicting what it’s like to live a experience different from your own. There are many lists of readings circulating on social media, here’s one list from the scholarly blog I follow. As, Tre Johnson reminds us, learning and listening is only effective when followed by action. Johnson writes:

The right acknowledgment of black justice, humanity, freedom and happiness won’t be found in your book clubs, protest signs, chalk talks or organizational statements. It will be found in your earnest willingness to dismantle systems that stand in our way — be they at your job, in your social network, your neighborhood associations, your family or your home. It’s not just about amplifying our voices, it’s about investing in them and in our businesses, education, political representation, power, housing and art.

Action will look very different for different people, depending on their inclination, ability, etc. For example, protests have never been appealing to me because of my social anxiety, even before COVID19 was a concern. However, there are more ways to act, such as donating to local organizations, donating to bail funds for protesters, signing online petitions, calling your local, state, and federal representatives and asking for action, support black-owned businesses in your area, etc. So, first: Read! Second, act in some way that works for you.

One final note, this post focused on race, but there are many other intersections to consider such as gender, ability, education, and orientation when it comes to being more inclusive.