I was given an assignment this week—to list all the library’s subscriptions from a particular journal publisher, then rank them according to their priority for TAMU-CC. The library subscribes to more than 2,700 of this publisher’s journals. How would you go about determining the relative importance of each one?

Obviously, your personal favorite journal should be at the top of the list, right? (Hang on, I’ll say more about that later.) But what about the rest?

As it happens, librarians like to count and measure different aspects of books. There’s a whole field devoted to this, called bibliometrics (literally, book-measuring). For example, you might count the number of citations in a book’s bibliography, or how many times a given book or article has been cited by other authors. Those metrics eventually led to a popular one called Journal Impact Factor™, and other citation measures such as Eigenfactor and h-Index.

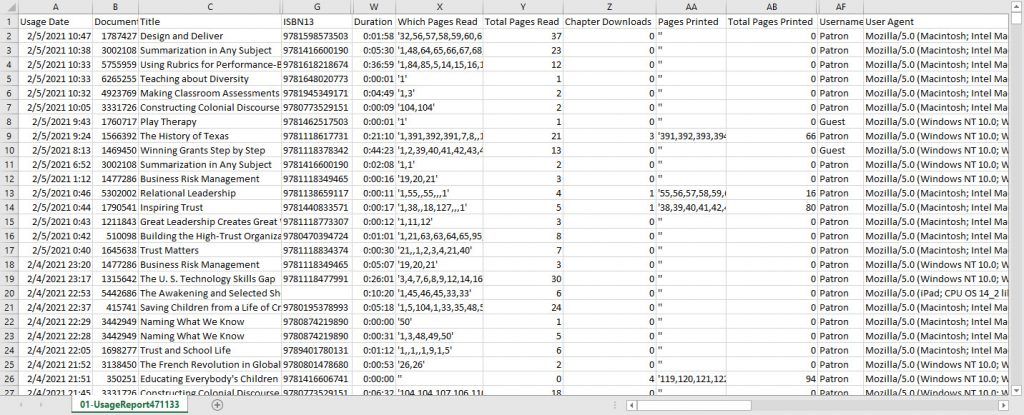

For printed library materials, it’s common to count circulation (how often a book has been checked out). For online library materials, computers can do the counting. Computers can count at a very granular level—not just how many times a book was “opened” online, but how much time the user spent reading the book, how many pages, and even which pages. By the way, don’t worry—we don’t track who the user was, just that somebody read the first 2 pages and stopped there.

But suppose you had to rank three journals, and all three were used 10 times during the past year. Then you might consider subscription cost. Taken together with usage, this leads to a common measurement called cost per use. If a journal costs $5,000/year (yes, some are that expensive) and gets used 10 times that year, the cost per use would be $500. This is an important metric because it allows you to see that even though a database or journal might be among your most expensive, it also might get used enough to make it a better value than less expensive products.

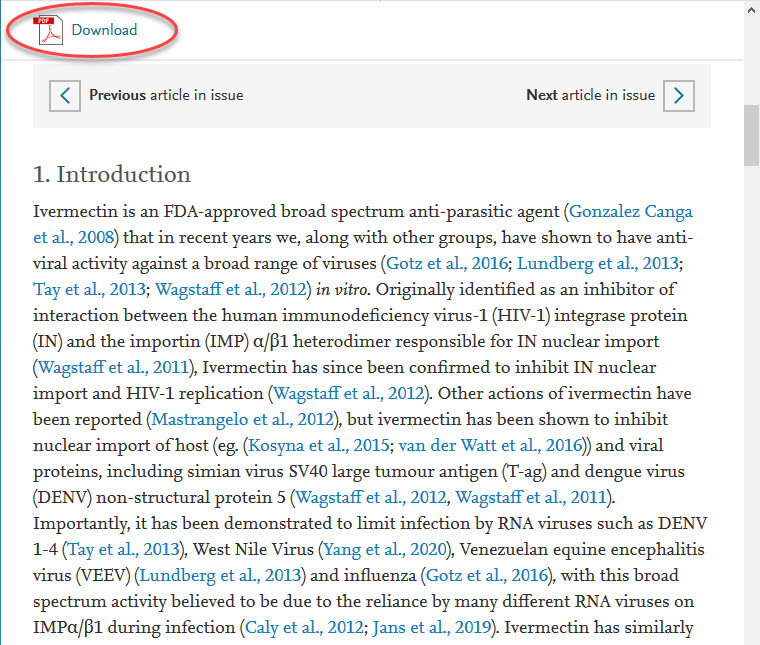

That brings us to a sort of apples-to-oranges problem—when calculating cost per use, what constitutes a “use”? For books and journals it might seem straightforward. Downloading an article from a journal is 1 “use,” right? But what if your browser pulls up the HTML version of an article, and then you download the PDF—The computer sees that as two article downloads, but should it count as two “uses”? And what would you count as “using” an e-book? Does each chapter download count as 1 use? Each page? Should reading 2 pages carry the same weight as reading 2 chapters, or the full book? Or what if a user reads chapter 1 in the morning and chapter 2 later that evening—Is that 1 use or 2?

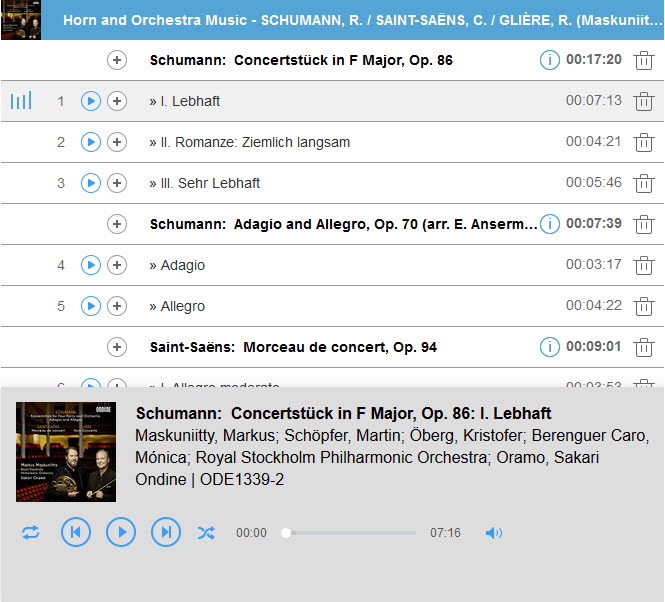

Non-text resources can be even more puzzling. How much of a streaming video should someone have to watch before it counts as one “use”? The whole film? Half? 60 seconds? If

someone uses the Naxos Music Library database to stream an album with 12 tracks, should that count as 1 use or 12 in your cost per use calculation? And how would you count the number of “uses” of a statistical database like SimplyAnalytics, where users add variables and generate reports?

With computers doing the counting, there are limitations. You have to be careful not to equate one type of “use,” like downloading a journal article, to another, like watching a streaming video. Moreover, counting algorithms and reporting software aren’t sophisticated enough to catch the nuances of deeper vs superficial use. To be fair, it isn’t all the computer’s fault. Even with something as simple as check-outs of print books, there’s no way to know whether the person who checked it out actually read the book, let alone found it useful.

As tempting as it is to settle on One Metric to Rule Them All and let Excel calculate journal priority for you, most librarians agree that it’s important to look at multiple metrics to try to get the full story. And despite the urge to quantify everything, sometimes a subjective measure is essential. The library frequently seeks input from faculty members when evaluating materials. Numbers can tell a lot of the story, but the researchers who actually use the materials will often add interesting twists to the plot.

So whenever a colleague asks me how much a book, journal, or database has been “used,” I often ask for clarification. What type of “use” do you want to know about? And I try to be precise in my own descriptions. Instead of talking in terms of cost per use, I try to be more specific and say “cost per check-out,” “cost per video play,” or “cost per article download.” This precision helps me understand the bigger picture, and hopefully be more fair when comparing different library resources.