While many residents of Corpus Christi are familiar with the German pioneer family of surveyors, the Blüchers, the famous family name also lived on in Germany simultaneously. The Blüchers had been landowners and nobility for hundreds of years when Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher was born in 1742, a little over 100 years before his kin would arrive on the unsettled Texas coast. Blücher would go on to match Paul von Hindenburg as the most highly decorated Prussian-German soldier in history. Blücher along with the Duke of Ellington struck the decisive blow at Waterloo that ended the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. As such, the family named was revered in Germany and used in honor to name three warships over a period of 60 years.

Sailing the ocean blue and superstition seem to go hand in hand. The Earth’s oceans can be one of the most deadly and unforgiving forces of nature that humankind regularly attempts to tame while going about its affairs. Add a couple of World Wars into the mix, and the potential for disaster increases exponentially. Yet even before the outbreak of World War I, the first ship named Blücher had already suffered destruction by a boiler explosion. With the outbreak of hostilities, the bad-luck-Blücher run would continue for each ship subsequently named after Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

The first Blücher ship was a Bismarck-class corvette launched in 1877. At 270 feet, SMS Blücher was utilized primarily as a torpedo training ship and went through several major refits. Despite being a training ship in a time of peace, on November 6, 1907, an improperly prepared boiler exploded, killing 16 men. Luckily, most of the crew had not been on the ship at the time of the explosion. The SMS Blücher was deemed unworthy of repair and sold to a private company. It was subsequently used as a coal storage hulk in Spain, and then it vanished into unknown history after 40 years of service.

The second Blücher warship was also named SMS Blücher. At 530 feet, it was nearly twice as long as the original SMS Blücher and it was also the last armored cruiser built by the German Empire, receiving its commission in 1909. In an attempt to outgun their British rivals, the Blücher was fitted with 12 8.3-inch guns in six twin turrets. Within a week of final construction being approved, intelligence about the new British Invincible class battlecruisers revealed that Blücher would be outclassed upon completion, yet construction continued. Despite being surpassed immediately by the new German and British battlecruisers at the outbreak of World War I in 1914, SMS Blücher was dispatched with a squadron to bombard the British ports of Scarborough, Hartlepool, West Hartlepool, and Whitby. Hartlepool, a major port had 1,150 shells rained down upon it, hitting steelworks, gasworks, railways, seven churches and 300 houses. 86 civilians were killed and 424 injured, drawing worldwide condemnation. The SMS Blücher was damaged by six hits from coastal defense batteries, resulting in nine deaths and three wounded. The damage was mostly superficial, but Blücher’s luck would not hold out in its next major engagement.

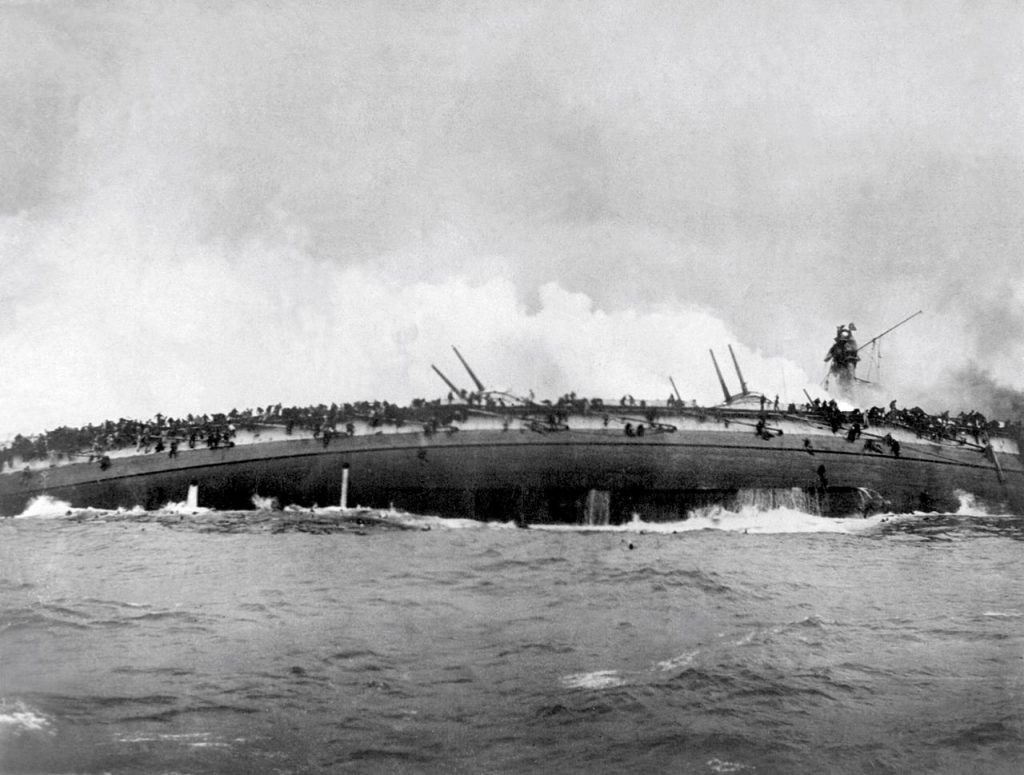

British cryptographers were able to intercept and decode German wireless signals after retrieving a German codebook. Determining operations would be conducted in the Dogger Bank region of the North Sea, the British sent five battlecruisers, seven light cruisers, and thirty-five destroyers to meet the Germans. The Germans in turn had three battlecruisers, one armored cruiser (SMS Blücher), four light cruisers, eighteen torpedo boats, and one zeppelin. The British surprised the German squadron, which fled, with SMS Blücher in the rear. The British ships were both faster and had longer range guns than their German counterparts. Additionally, visibility was impaired for the Germans due to their own funnel and gun smoke blowing backwards towards the advancing British. A shell penetrated Blücher, igniting an ammunition fire and damaging the boiler room, which caused Blücher to reduce speed. A miscommunication from Vice-Admiral David Beatty turned the entire British squadrons attention to Blücher rather than continuing to pursue the German fleet as intended. The German ship, not yet out of the fight, was able to hit the HMS Meteor’s boiler room, bringing it to a stop, but a relentless barrage of about 70 shells pulverized the SMS Blücher and it soon capsized. As the British moved in for rescue operations, the German zeppelin LZ-28 mistook the wreck for a British ship and began bombarding the British destroyers. Of a crew over 1,000, over 700 of the SMS Blücher’s crew were killed in its sinking. The battle resulted in the death or capture of over 1,000 German soldiers, with British losses of killed or wounded at less than 50. On a day that the entire German fleet could have been decimated in a surprise attack, Blücher was the only vessel on either side that was sunk.

With Nazi Germany openly defying the Treaty of Versailles twenty years later, construction began on a third Blücher. Upsizing from previous iterations continued, with the heavy cruiser coming in at 666 feet long. Blücher passed sea trials and was put into service on April 5, 1940. On April 8th, Blücher departed Germany as the flagship of a fleet tasked with capturing the capital of Norway, Oslo, King Haakon VII, Norway’s parliament, and their gold reserves. On April 9th it would lay at the bottom of Drøbak Sound.

As Blücher plowed its way toward Oslo, 64-year-old commander of Oscarsborg Fortress Colonel Birger Eriksen had no intel about the nationality of the warships. Norway was officially neutral at the time however, so the national identity of the ships soon became moot as they repeatedly ignored warning shots from coastal defense systems. Eriksen decided that although official Norwegian military policy was to fire warning shots unless fired upon, the previous shots from other defense positions and the warships persistence meant his battery could proceed without warning. Upon having his command to fire on Blücher questioned, Eriksen famously retorted “Either I will be decorated, or I will be court martialed. Fire!”

German intelligence had drastically underestimated the capabilities of Oscarsborg Fortress. Their main weapon system was an eleven-inch, three-gun combination that had been installed in the 1890’s and was considered a low threat to a heavy cruiser such as Blücher. This would prove a fatal mistake. The Battle of Drøbak Sound began with two direct hits on Blücher, one of which started a major fire which detonated explosives, oil, and depth charges and destroyed both Arado seaplanes the cruiser was carrying. Electricity to the vessels main guns was cut, rendering it unable to return fire. Soon thereafter, both steering and fire suppression systems were also inoperable.

At this point, as Blücher burned, a group of its sailors could improbably be heard singing Deutschland, Deutschland über alles, the German national anthem, finally revealing their identity to the Norwegians on Oscarsborg.

As if in response, Oscarsborg unleashed a weapons system German intelligence had no idea about. The eleven-inch guns were not the only thing installed in the 1890’s. An underwater torpedo battery had been built into a cave mined into the rock, capable of firing six torpedoes without reloading. The 40-year-old Austria-Hungary 100kg TNT weapons were called Whiteheads and were the first self-propelled torpedoes ever developed in 1866. This would be the last known operational use of this type of antique torpedo.

The first of two torpedoes did only superficial damage. With a minor adjustment in course, the second Whitehead was delivered with deadly accuracy, hitting Blücher amidships in nearly the same place as the shell that had done such extensive damage already. Bulkheads were blown apart, and fires soon reached an ammunition hold, which exploded and then ruptured the fuel bunkers. Blücher’s short life was over, and it slipped into the frigid Norwegian waters as what was left of its estimated crew of 2,000 attempted to abandon it. The leaking fuel and oil caught fire on the surface of the water, killing hundreds. Estimated deaths range from 650-800. After the other ships in the German fleet saw what had been done to their flagship, they retreated to fight another day.

The sinking of Blücher only delayed the inevitable fall of Oslo, but it gave King Haakon VII and parliament enough time to escape with the gold reserves, hampering Nazi efforts to exert any perception of legitimate power over the newly conquered territory and people. The wreck sits about two-hundred feet below the surface and began significantly leaking oil in the 1990’s. Salvage operations removed one thousand tons of oil, refined it, then sold it. An Arado 196 aircraft was also salvaged and is now on display at Flyhistroisk Museum, Sola. One of Blücher’s anchors now sits in the Aker Brygge area of Oslo. As of 2022, Germany has not named any naval vessels Blücher again.

Mary and Jeff Bell Library’s Special Collections & Archives Department has finished the processing of the Charles F.H. von Blucher Family Papers and is now working on digitizing select materials. The processing and digitization of these papers was made possible with two generous, successive grants from the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Eric Christensen

Special Collections and Archives, Librarian of Archive Processing